By Daniel Barringer, preserve manager.

Photo: Daniel Barringer

I have always said that November brings a special light. The sun angles lower, and though peak fall foliage is past, there is a lovely peach color in the air. In the photo above, it is remarkable that the sun shining through the base of the trees reveals that the hill is not nearly as tall as we think—the trees add a lot to the perceived height. That hill is located in Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site, part of the landscape of the Hopewell Big Woods, a large protected area of national, state, and county parks as well as preserves protected by nonprofit organizations like Natural Lands.

Photo: Daniel Barringer

Turning east at sunset offers another view that reminds me of the light captured in Maxfield Parrish paintings. Sunset illuminates puffy clouds low in an otherwise clear sky.

November light is also the stored energy of trees split for firewood. Most trees that fall we leave to nurture the soil and grow more trees, but some I cut up and give away as firewood. I also keep some for home.

Photo: Daniel Barringer

The family pets jockey for position in front of the wood stove. I can’t imagine having a wood stove without a window in the door. We enjoy the light as much as the heat, and that glow makes the darkness of winter much easier to bear.

By Kit Werner, Senior Director of Communications

Say the word “prairie,” and most of us picture the vast plains of the Midwest. In contrast, the northeastern U.S. is the land of would-be woods, where every farm field and meadow quickly reverts to forest without intervention. Yet early accounts of this region—“Penn’s Woods,” as colonists named it—reveal a far more nuanced picture of Pennsylvania’s native ecology. One that included thriving eastern prairies that evolved with fire.

Some 400 years ago, English explorers of the North American continent were met with awesome expanses of grasslands. With no word for this habitat type, they adopted the French term for meadow: prairie.

Contrary to the common belief that the northeastern U.S. was once entirely forested, historical accounts depict tall meadows and broad savannahs tended with fire by Indigenous communities. Regional placenames are another clue. Southwest Philadelphia’s Kingsessing is derived from the Lenape word for “place where there is a meadow.” The Wyoming Valley region around Wilkes-Barre takes its name from a corruption of the Indigenous word for “great meadows.”

Eastern prairies have long disappeared throughout their range in the face of farming and development. The removal of native people and their millennia-old relationships with the land—particularly, their seasonal controlled burns that held back trees and regenerated the grasslands—have further ensured the decline of these unique meadow ecologies.

On Natural Lands’ nature preserves, however, prairies are making a big comeback.

“Over the past decades, we’ve converted almost 1,000 acres of former farm fields to native grassland meadows,” said Gary Gimbert, vice president of stewardship. “

In 2025 alone, we installed meadows at ChesLen and Diabase Farm Preserves with a focus on pollinators, birds, and other wildlife that rely on this type of habitat for food, nesting, and—in the case of raptors—hunting sites.”

Grasslands are of particular importance to several species of native songbirds—including Bobolink, Eastern Meadowlark, and Grasshopper Sparrow—that build their nests on the ground, tucked between clumps of meadow grasses. With more and more land lost to development each year, grassland birds are really struggling, having lost a third of their numbers in the last half-century.

Meadows are also home to a vast array of nectar-rich wildflowers that support our native pollinators: bees, butterflies, moths, wasps, beetles, and flies.

“Over the years, we’ve learned a lot about how to create thriving meadows,” said Gary. “We can’t just plant grass and wildflower seeds and walk away. Meadows take regular maintenance, or they’ll be filled with invasives and eventually become forests.”

One important technique Natural Lands uses to keep its meadows healthy is fire. For 25 years, prescribed burns have been part of the organization’s comprehensive approach to land stewardship.

Many meadow species have evolved not only to withstand but also benefit from periodic burning. Two native grasses, big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) and little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), respond to fire by sprouting substantially more growth and setting more seeds. Fire stimulates the underground rhizomes of Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans) and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum).

The secret to these and other native grasses’ survival of fire is their deep roots; three quarters of the plant is underground. The visible plants are merely the photosynthetic leaves gathering sunlight. These deep roots make meadow plants valuable carbon sinks. Unlike forests, they don’t release that carbon when burned because most of the plant material is under ground.

“The results speak for themselves,” said Darin Groff, director of land stewardship and burn boss for Natural Lands’ prescribed fire crew. “We walk away from a burn with the plants charred black. But very quickly after, you can see life—meadow grasses sending up new shoots, seedlings sprouting, hawks circling overhead.”

Added Darin, “Controlled burns aren’t a short-term fix. Meadow management takes ongoing effort from our land stewardship team.”

Fortunately for the birds, bees, butterflies, and blooms, Natural Lands is in the business of forever and will keep tending the remaining eastern prairies in our care.

benefits of prescribed fire.

- Helps control the encroachment of woody plants and the growth of invasive species

- Helps remove the buildup of dried plant material, which reduces the risk of wildfires

- Improves the release of nutrients from dead plant material so that they can be recycled through the ecosystem

- Warms the soil in early spring by allowing more sunlight to reach the ash-darkened ground, increasing microbial activity, further helping to release nutrients from dead plant matter

- Improves and increases food and cover for wildlife, as new growth flushes after fires and attracts grazing animals

- Improves plant diversity

training & testing before ignition.

by Fateen Stafford, 21st Century Conservation Fellow

On an early morning in April, a crew dressed in yellow and green wildland fire gear starts prepping its equipment. The drip torches are refueled, the backpack pumps are checked for any leakage, and the hand tools are sharpened. All these items are loaded onto the back of trucks and all-terrain vehicles that have been specially outfitted with water tanks, pumps, and a few hundred feet of hose.

This is the start of a burn day at one of Natural Lands’ meadows.

But long before the first blades of grass are ignited, Natural Lands stewardship staff goes through significant training to be certified in the use of prescribed fire.

The process starts with study—about 40 hours of it to pass five courses covering equipment and terminology, the Incident Command System, and working with peers in a high-risk environment. Each year, the Natural Lands fire crew participates in this training, which culminates in a Work Capacity Test. Every participant must walk two miles in 30 minutes with a 25-pound vest on, to simulate the weight of fire-fighting gear. A Field Test requires physical demonstration of all the skills learned online.

After my training this past spring, I had the confidence to use the drip torch to light a section of meadow at ChesLen Preserve, use hand tools to scrape back the dried winter grass so that the fire would be contained when it hit the bare soil, and “mop up” at the end of the burn by spraying down smoldering areas.

So, the next time you visit a Natural Lands meadow, you’ll have a little sense of the work that goes in to keeping these habitats healthy. One fire at a time.

MEDIA, Pa., October 31, 2025 – Natural Lands announced today the addition of two adjacent, undeveloped parcels totaling 102 acres to its Bryn Coed Preserve in Chester Springs, Chester County. The newly acquired lots bring the total acreage of the nature preserve to just over 612 acres. The properties will be stewarded to benefit native plants and wildlife.

In the 1970s, the Dietrich family assembled the vast acreage known as Bryn Coed Farms one parcel at a time. One of these tracts was the former homestead of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts, who named his farm “Bryn Coed,” which means “wooded hill” in Welsh.

Many worried over the fate of the pristine farmland and forests—located just 30 miles northwest of Philadelphia—as development pressures increased in the region. In 2018, Natural Lands acquired the entirety of the 1,505-acre property to protect it from large-scale development. The organization created a 510-acre nature preserve at the heart of the property and partnered with West Vincent Township, which created the 72-acre Opalanie Park immediately adjacent to the preserve. Natural Lands preserved the remainder of the land by selling large-acreage lots, each under permanent conservation easement, to conservation-minded buyers.

Donors who wish to remain anonymous have gifted two of those lots back to Natural Lands to increase the size of the preserve and, ultimately, to make more of this important landscape available for public recreation. The parcels consist of gently rolling fields, forest, and hedgerows.

Said Natural Lands President Oliver Bass, “Saving Bryn Coed was the chance of a lifetime, and we’ve benefitted mightily from the support of devoted partners, funders, and donors. This extraordinary gift of an additional 102 acres will expand both the footprint and the benefits of the preserve for generations to come.”

He added, “I have such respect for Preserve Manager Darin Groff and Assistant Preserve Manager Caleb Arrowood, who have transformed Bryn Coed into a thriving nature preserve filled with native plants. They will steward these new parcels with the same care and passion, and we’ll all reap the benefits of their work.”

“It’s very exciting to add additional acreage to the preserve,” said Darin Groff, director of land stewardship. “Over the next couple of years, we will be planting wildflower meadows for pollinator habitat and additional grasslands, and work to connect wooded areas to one another by planting additional trees.”

Natural Lands is dedicated to preserving and nurturing nature’s wonders while creating opportunities for joy and discovery in the outdoors for everyone. As the Greater Philadelphia region’s oldest and largest land conservation organization, Natural Lands—which is member supported—has preserved more than 136,600 acres, including 40+ nature preserves and one public garden totaling more than 23,600 acres. About five million people live within five miles of land under the organization’s protection. Land for life, nature for all. natlands.org.

Please note: “Natural Lands” is the organization’s official operating name and should be used instead of its legal designation (Natural Lands Trust, Inc.).

Media Inquiries:

Kit Werner, Senior Director of Communications

610-353-5587 ext. 267

###

By Kit Werner, senior director of communications, and Tianna Godsey, events manager

turning fear into facts.

As Halloween approaches, we thought it was a good time to highlight the native bats of Pennsylvania. Though sometimes considered spooky or frightening, these remarkable mammals are no threat to people. In fact, they are beneficial to us all.

There are nine common bat species in Pennsylvania: big brown, little brown, tricolored, small-footed, long-eared, silver-haired, hoary, eastern red, and Indiana. They range in size from about 15 inches for the hoary bat down to the tiny Indiana bat, which is only about the size of your thumb.

Big brown bats are the most commonly seen in our region, usually just after sunset or right before sunrise during feeding time. They eat agricultural pests, like June and cucumber beetles, and stinkbugs; they also eat ants, stoneflies, mayflies, lacewings, mosquitos, and, occasionally, moths. A small colony of 25 bats can eat a pound of insects every night.

The Ancient Greek word for bat, chiroptera, means “hand wing.” This apt name comes from the animal’s elongated fingers that make up the main structure of the wings. A delicate skin membrane, called the chiropatagium, spans digits two through five. By moving their fingers, they can control the movement of their wings, offering these animals far more flight agility and efficiency than birds or insects.

Big brown bats typically live between six to 19 years in the wild. But bats as an order have been around for centuries. In fact, the oldest fossilized bat ever discovered (found in Wyoming) is an estimated 52 million years old.

Female bats give birth to pups upside down. Most bats only have one pup at a time, largely because the young are born weighing almost a third of their mother’s weight, which means she needs to use a lot of energy to keep them fed, nursing them until they are weaned and transition to insects. Mother bats often fly with their pups. The young cling to their mother’s underarm nipple with their mouths and hang onto her waist with their toes.

While vampire bats are real, they are not present in our region. They live primarily in Central and South America, with some species found in Mexico and the southern U.S. They generally feed on the blood of livestock like cattle, not humans.

Bats can carry rabies, but the incidence of rabies in bats is extremely low—less than one percent—and not a reason to fear these remarkable creatures.

If you want more bats around for natural insect control, skip bat boxes. They generally don’t work to attract bats and can spread disease. Instead, turn off your lights at night and plant lots of native plants, which, in turn, attract native insects.

If you can handle the cuteness, check out this video of a hoary bat named Astrid being fed mealworm grubs at our Bat Bonanza event at Mariton Wildlife Sanctuary. Pennsylvania Bat Rescue is caring for her for the rest of her life as she only has one wing and cannot be released.

By Kit Werner

Before we talk about autumn’s arboreal display, let’s have a mini science lesson.

There are several types of pigment in leaves:

- Chlorophyll (green)

- Xanthophylls (yellows)

- Carotenoids (oranges)

- Anthocyanins (reds)

- Tannins (browns)

These pigments are always present in the trees’ leaves but are hidden by green chlorophyll spring and summer. In fall, shorter days and less sunlight are signals for trees to stop making chlorophyll and prepare for dormancy. As the green fades, the reds, oranges, and yellows become visible. Because they do not fade, brown tannins are the last colors to remain in a leaf before it falls.

Peak leaf peeping in southeastern Pennsylvania generally occurs in mid-October, though weather impacts both timing and the intensity of the color display. However, there are some native plant species that never fail to deliver vibrant fall leaf color, regardless of drought, deluges, and cold snaps. Here are a few of our favorites:

Trees:

- Black gum (Nyssa sylvatica)

- Pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

- Smoketree (Cotinus obovatus)

- Sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum)

- American Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua)

- Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida)

Shrubs:

- Virginia Sweetspire (Itea virginica)

- Witch-Alder (Fothergilla spp.)

- Sumac (Rhus spp.)

Perennials/Vines:

- Bluestar (Amsonia hubrichtii)

- Spotted Cranesbill (Geranium maculatum)

- Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Happy fall, y’all! Now get out there into the woods and enjoy the autumn show while it lasts.

- Cornus florida ‘Appalachian Spring’ – Photo: David Korbonits

- Itea virginica – Photo: Sam Nestory

- Amsonia hubrichtii ‘String Theory – Photo: Sam Nestory

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia – Photo: Jill Sabre

- Fothergilla gardenii ‘Blue Elf’ – Photo: David Korbonits

- Geranium maculatum – Photo: David Korbonits

- Rhus typhina ‘Ivin’s Chartreuse’ – Photo: David Korbonits

- Nyssa sylvatica – Photo: Sam Nestory

- Asimina triloba – Photo: Sam Nestory

- Cotinus obovatus – Photo: David Korbonits

- Oxydendrum arboretum – Photo: David Korbonits

- Liquidambar styraciflua – Photo: Sam Nestory

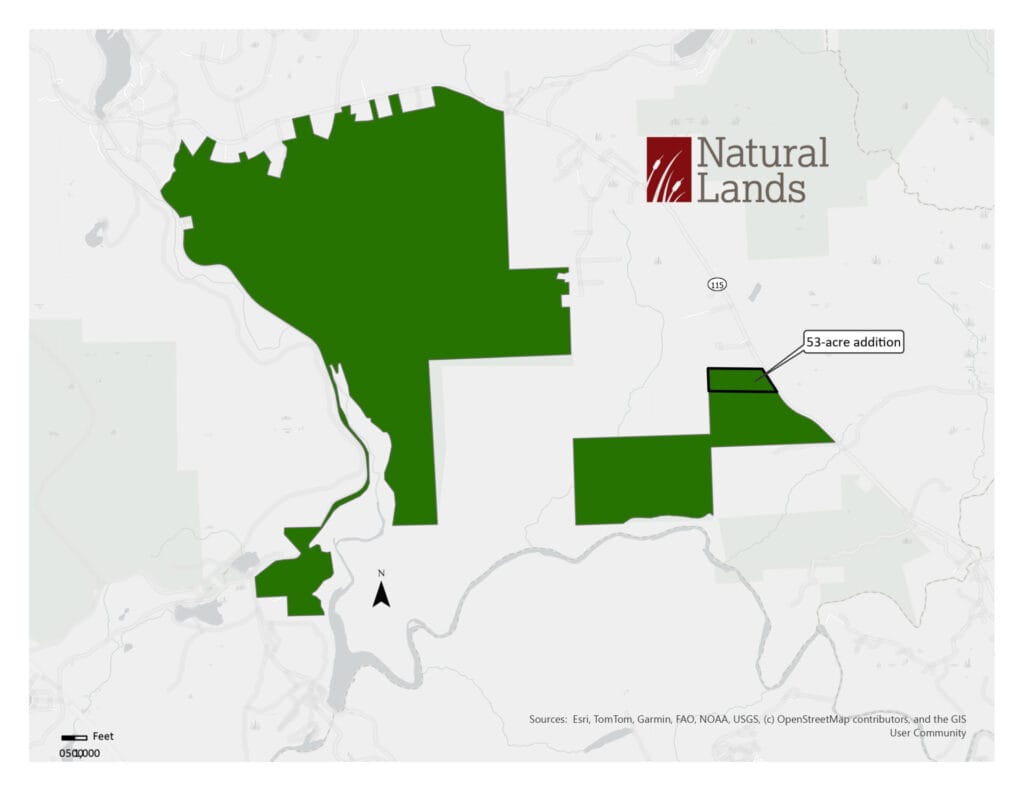

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

MEDIA, Pa., August 4, 2025 – Natural Lands announced today the addition of a 53-acre property to its Bear Creek Preserve in Buck Township, Luzerne County, PA. The forested land, located immediately adjacent to the now 3,986-acre nature preserve, will be managed for ecological health, species diversity, and public recreation. Bear Creek Preserve is open to the public, free of charge, from dawn to dusk every day except Mondays.

“For generations, this property has been maintained as woodlands,” said John Brislin, representing the Corgan family. “Selling the property to Natural Lands to become part of Bear Creek Preserve was an easy decision as a way to help preserve the Lehigh Valley watershed and to make this land available to people to enjoy for generations to come.”

Bear Creek Preserve, one of more than 40 nature preserves in Natural Lands’ care, is part of a vast mosaic of protected lands including state game lands, Bureau of Forestry property, and private conservation easements. As part of Bear Creek Preserve, this once-vulnerable property will never be developed.

“Bear Creek Preserve is part of a larger landscape of protected open space, including state parks and game lands, that spans more than 150,000 acres,” said Jack Stefferud, Natural Lands’ senior advisor for land protection. “Seventy percent of Pennsylvania’s forests are privately owned, which means they are vulnerable to development. We are grateful to the Corgan family for choosing to preserve their land by selling it to Natural Lands.”

More than half of the newly acquired property falls within the “Dry Land Hill Pools,” a special designation determined by the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. The large vernal pools—which appear in spring but dry up as the weather warms—are set within an oak-dominated forest, an area usually quite dry.

The area is home to two “species of concern”: the few-seeded sedge (Carex oligosperma) and the Bog Copper butterfly (Lycaena epixante), the latter of which uses cranberry as its larval host plant. Wetlands, including ephemeral pools, serve as nature’s living water filters. Water moving downstream slows as it passes through wetlands, allowing time for it to be reabsorbed into the ground. Plants growing in the wetlands break down contaminants, filter out sediment, and store excess nutrients like carbon dioxide. Insects, plants, and animals—including people—benefit from the water cleaning services that wetlands provide, free of charge.

These boggy habitats are home to more plants, bugs, birds, frogs, fish, and invertebrates than any other habitat on Earth. More than half the plants and animals in Pennsylvania rely on wetlands for food and reproduction. Yet, in the past 200 years, more than half of all the wetlands in Pennsylvania have been lost to development.

The Allerton Foundation provided support for this project.

Natural Lands is dedicated to preserving and nurturing nature’s wonders while creating opportunities for joy and discovery in the outdoors for everyone. As the Greater Philadelphia region’s oldest and largest land conservation organization, Natural Lands—which is member supported—has preserved more than 136,600 acres, including 40+ nature preserves and one public garden totaling more than

23,600 acres. About five million people live within five miles of land under the organization’s protection. Land for life, nature for all. natlands.org.

Please note: “Natural Lands” is the organization’s official operating name and should be used instead of its legal designation (Natural Lands Trust, Inc.).

Media Inquiries:

Kit Werner, Senior Director of Communications

610-353-5587 ext. 267

###

MEDIA, Pa., July 28, 2025 – Natural Lands announced today the completion of an ADA-compliant trail at its Sadsbury Woods Preserve in Coatesville, Chester County. The trail will enable greater access to the preserve for visitors with varying mobilities.

Visitors can access Sadsbury Woods Preserve’s ADA trail from the parking lot at 443 Old Wilmington Road and follow it into the woodland for about .11 miles. Trail users will be able to view the preserve’s rain garden—which filters runoff from the parking lot into a beautiful and purposeful planting of water-loving species, a large reforestation area with hundreds of native tree seedlings, and the towering woodlands that define Sadsbury Woods Preserve. At the entrance to the forest, visitors can relax on a pair of benches made from a large chestnut oak that blew down in a storm.

“Visitors can listen to the birdsong and look for a range of bird species,” said Preserve Manager Erin Smith. “The preserve is part of the largest remaining unbroken forest in Chester County. These woods provide critical habitat to songbirds, especially neotropical migrants that winter in South America and breed in our region. To survive, they need food and protection from weather and predators—all things the preserve’s forests provide.”

The trail is particularly enchanting in spring with a carpet of ephemeral wildflowers. Visitors can enjoy an ever-changing display of species: mayapple, bloodroot, spring beauty, wild geranium, hepatica, and Jack-in-the-pulpit.

“Natural Lands is committed to stewarding the open spaces under our care to ensure their conservation value and also to provide outstanding experiences in nature to our hundreds-of-thousands of visitors,” said Natural Lands President Oliver Bass. “We are eager to improve accessibility through strategic infrastructure improvements such as this trail at Sadsbury Woods.”

Information about what to expect at each of our nature preserves and at Stoneleigh: a natural garden can be found at natlands.org/accessibility.

This project—and so much more—is enabled through the support of Natural Lands’ members. To learn more, visit natlands.org/join.

Natural Lands is dedicated to preserving and nurturing nature’s wonders while creating opportunities for joy and discovery in the outdoors for everyone. As the Greater Philadelphia region’s oldest and largest land conservation organization, Natural Lands—which is member supported—has preserved more than 136,600 acres, including 40+ nature preserves and one public garden totaling more than 23,600 acres. About five million people live within five miles of land under the organization’s protection. Land for life, nature for all. natlands.org.

Please note: “Natural Lands” is the organization’s official operating name and should be used instead of its legal designation (Natural Lands Trust, Inc.).

Media Inquiries:

Kit Werner, Senior Director of Communications

610-353-5587 ext. 267

###

By Daniel Barringer, Preserve Manager.

I have a lot more to write about highlights from the last five weeks of summer camp, but want to focus here on improvements to the trails. Our 7th and 8th grade summer campers built a section of boardwalks and bridge near the kids’ play area along Pine Creek, near the wire bridge over the creek. This protects the environment and improves visitor experiences.

We’ve had about the wettest summer ever—one reason there hasn’t been much time to write blog entries. Some of the trails are still wet but we’re doing what we can to make them passable.

Photo: Serena Hertzog.

When trails are wet, visitors should still stick to them. Those are the principles of Leave No Trace and Tread Lightly! campaigns and a way to protect the environment here and everywhere. Our Creek Trail has gravel embedded on it so there’s traction even when wet. If you leave the trail to go around the water, not only is the ground there softer—there is no gravel there—but you may trample sensitive vegetation and make the trail needlessly wide and muddy.

That’s why boardwalks and footbridges are good for visitors and for the environment next to the trails: People can keep their feet dry and the impact on the preserve from the trails is kept to a minimum.

Photo by Serena Hertzog.

Campers in our 7th and 8th grade programs have been coming here for years. Our youngest campers become comfortable outdoors in just one part of the preserve—the very location where these boardwalks are being built. As they return as older campers they come to know all 712 acres of Crow’s Nest Preserve. They demonstrate this by embarking on the Crow’s Nest Challenge Hike—a camper-led hike through the entire preserve. By the time they attend the oldest camp, they go on field trips to other Natural Lands’ preserves to see how Crow’s Nest fits into this conservation network. They also give back to the preserve through service projects like building these boardwalks and bridge.

By Preserve Manager Jarrod Shull.

In May, 2025, we completed a large-scale tree planting project at our Peacedale Preserve in Landenberg, Chester County, PA. With the help of contractors, we planted 11,020 native seedlings along waterways and across 36 acres of former fields. Over time, the seedlings will mature to a diverse forest, offering habitat for wildlife and improve water quality.

The creeks that travel through Peacedale Preserve flow to Big Elk Creek, onward to Elk River, and empty into Chesapeake Bay. About 2,700 plant and animal species live in the Chesapeake Bay Estuary, and fishermen harvest around 500 million pounds of seafood from the Bay every year.

Natural Lands is committed to creating and maintaining a minimum 100-foot buffer along all waterways that run through our nature preserves. As they mature, the native trees we’ve planted at Peacedale will help filter out sediment and other pollutants, reduce erosion, and slow stormwater to prevent flooding.

map of Peacedale Preserve with tree planting locations in green

When Europeans first explored Pennsylvania, trees covered 90 percent of the territory. Though the Native Americans who had lived in the region for thousands of years did clear some land for hunting and agriculture, famed naturalist John Bartram still found forests so thick it was “as if the sun had never shown on the ground since the creation.” But by 1850, millions of acres had been cleared for farming, timber, and firewood.

In addition to improving water quality, the tree planting project at Peacedale Preserve will re-establish forest cover and improve wildlife habitat. In particular, woodlands are essential for migratory songbirds—such as Scarlet Tanager and Wood Thrush—that rely on the dense forest for food and protection from the weather and predators.

Installing that many trees and the photodegradable tubes they need to protect them from the deer is a pretty involved project! We hired contractors to drill holes and plant the trees, but our staff had to prep everything to be ready for their arrival in late May.

The first step involved ordering the seedlings, tree tubes, and wooden stakes. The tubes arrived in the fall of last year… 18,000 of them. We stored them in the old stone barn at nearby Stroud Preserve.

18,000 photodegradable tree tubes delivered to Stroud Preserve | Photo: Jarrod Shull

Stewardship staff members unload tree tube bundles into the barn at Stroud. | photo: Jarrod Shull

Tree tubes stacked for short-term storage at Stroud | Photo: Jarrod Shull

When the seedlings arrived in mid-March, we stored them at Stroud Preserve’s barn, too, since there is room there and I live at the preserve and could water the trees regularly. Several preserve stewardship staffers helped unload the truck… 440 flats of 11,020 seedlings. The seedlings are a variety of native species, including red maple, silver maple, hornbeam, redbud, tuliptree, blackgum, sycamore, white oak, swamp white oak, pin oak, chestnut oak, elderberry, and flowering dogwood.

Staff unloaded tree seedlings at Stroud Preserve. | Photo: Jarrod Shull

11,200 tiny native tree seedlings in 440 flats stacked up outside the Stroud Preserve barn | Photo: Jarrod Shull

Just a few weeks later, the wooden stakes were delivered to Peacedale Preserve. We unloaded them with a forklift, and then drove the pallets of stakes to the three planting locations at the preserve, and covered them with tarps. We also covered the seedlings that same day, as there was frost predicted overnight.

Wooden stakes arrive on pallets | Photo: Jarrod Shull

We used a telehandler to move the pallets of stakes to three locations at Peacedale. | Photo: Jarrod Shull

Next it was time to move all those plastic tree tubes from Stroud out to Peacedale. We needed to load both the bed of the pick-up truck and a trailer to get them all out to the three planting locations.

Tree tubes loaded up for the drive to Peacedale Preserve | Photo: Jarrod Shull

And, finally, in mid-May we moved all those seedlings, which had really grown over the two months since they were shipped to us. We stacked the flats two or three high using boards and plywood to create levels inside the truck.

The seedlings have grown in the few weeks they were stored at Stroud. | Photo: Jarrod Shull

Loading the seedlings into the truck with plywood to separate them in levels | Photo: Jarrod Shull

We marked out and flagged the property lines, rights-of-way, and the planting areas for the contractors, who arrived on May 19 with a 21-person crew. It took three days for the crew to complete the planting, tubing, and staking of all 11,020 trees and shrubs. They were planted in 12-foot rows, wide enough to allow stewardship staff to mow between them, reducing competition from other vegetation until the seedlings have matured.

The rows will become less obvious over time as some trees naturally won’t survive. | Photo: Jarrod Shull

Natural Lands plans addition large-scale reforestation projects at several other nature preserves under their care, including Diabase Farm Preserve (New Hope, PA), Sadsbury Woods Preserve (Parkesburg, PA), and Stroud Preserve (West Chester, PA). By the close of 2025, the organization will have planted 22,540 trees and shrubs on 75.5 acres in just one year.

Funding for this project was provided by the E. Kneale Dockstader Foundation; the Conservancy Grant Program, Commissioners of Chester County, Pennsylvania; and donors to Natural Lands’ preserve restoration fund.

Watch the before and after planting video.

Fireflies are amazing insects! Did you know…?

- Fireflies and lightning bugs are the same thing! It’s just a different dialect and depends on where you grew up.

- Neither a fly nor a bug, fireflies are beetles in the order Coleoptera, family Lampyridae.

- There are 2,000 species of fireflies worldwide, 125 in North America, and 15+ in Pennsylvania.

- All fireflies emit some sort of bioluminescence at some point in their life cycle (every single firefly larva glows, aka “glow-worms”).

- There is fossil evidence of their light organ from 99 million years ago.

- Fireflies are diverse eaters; they can be cannibals, carnivores, and even nectar drinkers.

- Many fireflies exist in temperate, tropical habitats. In PA, you’ll find their peak is warm, humid nights in mid-June to early July. Once the night temps hit 60 F, they are less active.

- Adult fireflies only live for a few weeks. In their final moments, they will mate and lay eggs (when you’ll see their glow).

- Folklore incorporates fireflies as a spiritual symbol. Amazonian folklore tells that firefly light came from the gods, a symbol of hope and guidance. In Japanese legend, the light of two species represents ghosts of ancient warriors, or stars that left the sky to travel Earth. In Apache mythology, fire came to the people from trickster fox, who tried to steal it from the firefly village. Some cultures believe they are bad luck. In Victorian superstition, finding a firefly in your home meant someone would die soon.

- Fireflies glow through the enzyme luciferase, which catalyzes the oxidation of a luciferin, an organic substance, present in luminescent organisms.

- Scientists have employed luciferase to detect metabolic diseases, perform cancer research, test for life on Mars, in forensics, and to detect E. Coli and Salmonella in foods.

- Fireflies glow for different reasons, including warning of toxicity as larva, mating selection, and predation.

- The light produced by fireflies is the most efficient lighting in the world. It’s a cold light, emitting zero heat and no infrared or UV frequencies.

- Some things we can do to help dwindling and threatened firefly populations: plant native species; leave the leaves; reduce light pollution; avoid pesticides and herbicides.

Photo: Edward Harding