By Kit Werner

Before we talk about autumn’s arboreal display, let’s have a mini science lesson.

There are several types of pigment in leaves:

- Chlorophyll (green)

- Xanthophylls (yellows)

- Carotenoids (oranges)

- Anthocyanins (reds)

- Tannins (browns)

These pigments are always present in the trees’ leaves but are hidden by green chlorophyll spring and summer. In fall, shorter days and less sunlight are signals for trees to stop making chlorophyll and prepare for dormancy. As the green fades, the reds, oranges, and yellows become visible. Because they do not fade, brown tannins are the last colors to remain in a leaf before it falls.

Peak leaf peeping in southeastern Pennsylvania generally occurs in mid-October, though weather impacts both timing and the intensity of the color display. However, there are some native plant species that never fail to deliver vibrant fall leaf color, regardless of drought, deluges, and cold snaps. Here are a few of our favorites:

Trees:

- Black gum (Nyssa sylvatica)

- Pawpaw (Asimina triloba)

- Smoketree (Cotinus obovatus)

- Sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum)

- American Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua)

- Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida)

Shrubs:

- Virginia Sweetspire (Itea virginica)

- Witch-Alder (Fothergilla spp.)

- Sumac (Rhus spp.)

Perennials/Vines:

- Bluestar (Amsonia hubrichtii)

- Spotted Cranesbill (Geranium maculatum)

- Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

Happy fall, y’all! Now get out there into the woods and enjoy the autumn show while it lasts.

- Cornus florida ‘Appalachian Spring’ – Photo: David Korbonits

- Itea virginica – Photo: Sam Nestory

- Amsonia hubrichtii ‘String Theory – Photo: Sam Nestory

- Parthenocissus quinquefolia – Photo: Jill Sabre

- Fothergilla gardenii ‘Blue Elf’ – Photo: David Korbonits

- Geranium maculatum – Photo: David Korbonits

- Rhus typhina ‘Ivin’s Chartreuse’ – Photo: David Korbonits

- Nyssa sylvatica – Photo: Sam Nestory

- Asimina triloba – Photo: Sam Nestory

- Cotinus obovatus – Photo: David Korbonits

- Oxydendrum arboretum – Photo: David Korbonits

- Liquidambar styraciflua – Photo: Sam Nestory

Fireflies are amazing insects! Did you know…?

- Fireflies and lightning bugs are the same thing! It’s just a different dialect and depends on where you grew up.

- Neither a fly nor a bug, fireflies are beetles in the order Coleoptera, family Lampyridae.

- There are 2,000 species of fireflies worldwide, 125 in North America, and 15+ in Pennsylvania.

- All fireflies emit some sort of bioluminescence at some point in their life cycle (every single firefly larva glows, aka “glow-worms”).

- There is fossil evidence of their light organ from 99 million years ago.

- Fireflies are diverse eaters; they can be cannibals, carnivores, and even nectar drinkers.

- Many fireflies exist in temperate, tropical habitats. In PA, you’ll find their peak is warm, humid nights in mid-June to early July. Once the night temps hit 60 F, they are less active.

- Adult fireflies only live for a few weeks. In their final moments, they will mate and lay eggs (when you’ll see their glow).

- Folklore incorporates fireflies as a spiritual symbol. Amazonian folklore tells that firefly light came from the gods, a symbol of hope and guidance. In Japanese legend, the light of two species represents ghosts of ancient warriors, or stars that left the sky to travel Earth. In Apache mythology, fire came to the people from trickster fox, who tried to steal it from the firefly village. Some cultures believe they are bad luck. In Victorian superstition, finding a firefly in your home meant someone would die soon.

- Fireflies glow through the enzyme luciferase, which catalyzes the oxidation of a luciferin, an organic substance, present in luminescent organisms.

- Scientists have employed luciferase to detect metabolic diseases, perform cancer research, test for life on Mars, in forensics, and to detect E. Coli and Salmonella in foods.

- Fireflies glow for different reasons, including warning of toxicity as larva, mating selection, and predation.

- The light produced by fireflies is the most efficient lighting in the world. It’s a cold light, emitting zero heat and no infrared or UV frequencies.

- Some things we can do to help dwindling and threatened firefly populations: plant native species; leave the leaves; reduce light pollution; avoid pesticides and herbicides.

Photo: Edward Harding

One seed at a time, these volunteers are growing plants to increase the biodiversity both at Stoneleigh and yards, gardens, and patio planters across the region.

It’s Wednesday and a group of five volunteers gather in Stoneleigh’s greenhouse around a table piled high: bags of potting soil, plastic plant pots of varying sizes, trowels and tweezers, seedlings in tiny pots, and glassine bags filled with seeds of various kinds. The conversation is lively as they work methodically, transferring the seedlings from their starter pots to larger containers—a process known as “up-potting”—and placing seeds in grow trays filled with soil.

These are the Stoneleigh Potstickers, a humorous name they gave themselves as most of their work is to stick seeds or small plants in pots. When the plants get bigger, they stick them in larger pots, repeating this process until the plants are large enough to install outdoors or be sold at the annual Stoneleigh Native Plant Sale.

Though the work might sound tedious and monotonous, the Potstickers look forward to their Wednesday gatherings, which occur year-round.

“In the colder months, we spend time cleaning seeds,” explains Lin Hall, who proudly notes she was the original Potsticker. Stoneleigh’s Director, Ethan Kauffman, wild-collects seed from Natural Lands’ preserves and other places. The volunteers take apart the dried seed heads, separating the seeds from the chaff, sometimes using tweezers and magnifying lenses.

Like the other Potstickers, Lin fell in love with Stoneleigh after a visit some years ago. Her first volunteer role was as a Stoneleigh Ambassador, greeting guests when they arrive and helping orient them to the garden.

Photo: Lindsay Laban

“I’m big on education,” Lin shared. “As an Ambassador, I get to talk to people about the importance of native plants. But what better way to experience the beauty and benefit of natives than to grow some in your own yard? So many of the plants we pot up and care for are sold at the Plant Sale, which brings me great joy. I have some physical limitations, but as a Potsticker I can still get my hands in the dirt.”

Fellow volunteer Martha Van Artsdalen agreed. A former writer and garden columnist, Martha loves that she can brush up on her Latin species names as she works. “We get to keep learning—from each other and the Stoneleigh staff. It’s such a positive experience.”

Martha particularly enjoys opening the brown paper lunch bags that Ethan uses to collect the wild-collected seed heads. “Cleaning the seeds is hard work but opening those bags with all those different species… it’s like Christmas morning!”

This tightknit group of volunteers used the old Stoneleigh greenhouse as their workspace for several years, which was cramped quarters. “You get to know each other well when you work in such a small space together,” Lin shared. “We have such camaraderie and regularly get together socially outside of our volunteer work.”

Built in 1935, Stoneleigh’s estate greenhouse was originally designed for vegetables and houseplants. Though this building served the garden well, Stoneleigh’s ongoing evolution as a public garden requires new infrastructure.

In late 2024, the old greenhouse was demolished to make way for a new one that will improve energy efficiency, increase production capacity, and host new programs.

The greenhouse is slated to be completed later this summer, and the Potstickers can’t wait to ramp up their work. Thanks in part to the Potstickers, the Plant Sale offerings have really grown over the years; in 2025, there were more than 280 different varieties for sale.

Said Lin, “Stoneleigh has given so much to me and others who visit. Volunteering is my way of giving back. These little seedlings are my babies. It’s rewarding to see them grow. As a Stoneleigh volunteer, I’ve grown, too.”

While this volunteer opportunity is at capacity, Stoneleigh welcomes new volunteers every Tuesday and Thursday, beginning at 8:30 AM. Garden tasks include weeding, mulching, planting, and other seasonal projects. No experience necessary. Visit natlands.org/gardenhelp to learn more and register.

By Kit Werner, Senior Director of Communications.

For more than five years, many watched nervously as the Lower Merion School District (LMSD) explored plans to build athletic fields on 13 acres adjacent to Stoneleigh: a natural garden. Instead, in August 2024, Natural Lands and LMSD entered into an agreement allowing Natural Lands to acquire 10 acres of the site—known as Oakwell—to expand Stoneleigh and reunite these properties that were once one. The remaining three acres will be sold to a separate non-profit organization that intends to conserve those acres and restore the historical buildings they contain.

The agreement of sale is the first step in what will be a lengthy process. “Conservation projects like this one have many moving parts and take time and patience,” said Natural Lands President Oliver Bass. “This is just the first step, albeit an essential one.”

Under the plan, the additional acreage would create space for expansive new garden areas at Stoneleigh and provide more opportunities to showcase the beauty and benefits of gardening in an ecologically sustainable way. Early 20th century landscape designs by the famed Olmsted Brothers span both properties and would be connected again for the first time since Oakwell was subdivided in the 1930s.

The buildings on the property would be restored and adapted, creating exciting improvements to the guest experience at Stoneleigh. As Stoneleigh is now, the portion that Natural Lands seeks to acquire would be placed under conservation easement with the Lower Merion Conservancy.

“We are thrilled to have the opportunity to expand Stoneleigh and immensely grateful to the leadership of the Lower Merion School District,” added Oliver. “They have worked diligently with us to explore options for the property. Together, we’ve identified a plan that, if successful, will preserve the important natural and historic resources—including the much-loved trees and mansion—and grow Stoneleigh from its current 42 acres to more than 52.”

VILLANOVA, Pa., August 20, 2024 – Natural Lands and Lower Merion School District (LMSD) announced today that the LMSD Board of Directors has authorized the sale of the 13-acre site in Villanova, PA, known as Oakwell. The property is directly adjacent to Natural Lands’ Stoneleigh: a natural garden. Natural Lands is the intended buyer for approximately 10 acres of the property, which would expand Stoneleigh and reunite two important landscapes. The buyer for the remaining three acres—including Oakwell mansion, which would be restored—is a separate non-profit entity whose use will be complementary to Stoneleigh.

LMSD purchased the properties at 1800 W. Montgomery Avenue and 1835 County Line Road in 2018 as a site for athletic fields for Black Rock Middle School. In response to community sentiment for preservation of those properties (“Oakwell”), in January 2023, Haverford Township, Lower Merion Township, and LMSD announced an agreement to allow baseball and softball teams from Black Rock Middle School to have priority use of two fields on the Polo Field, located at 109 County Line Road in the Bryn Mawr section of Haverford Township. With the addition of these fields, as well as continued use of Gladwyne Park, the District is confident that the needs of our athletic teams at Black Rock Middle School are currently being met.

The Board’s resolution makes way for an agreement of sale, the first step in what will be a lengthy process. “Conservation projects like this one have many moving parts and take time and patience,” said Natural Lands President Oliver Bass. “This is just the first step, albeit an essential one.”

“We are thrilled to have the opportunity to expand Stoneleigh and immensely grateful to the leadership of the Lower Merion School District,” added Bass. “They have worked diligently with us to explore options for the property. Together, we’ve identified a plan that, if successful, will preserve the important natural and historic resources—including the much-loved trees and mansion—and grow Stoneleigh from its current 42 acres to more than 52.”

Kerry Sautner, president of the Lower Merion Board of School Directors, said, “We are proud to have partnered with Natural Lands and the Township in a shared commitment to preserving the Oakwell site. This agreement reflects our dedication to environmental stewardship and our responsibility to honor the community’s and students’ desire to protect and cherish our natural spaces. Through collaboration, we can achieve outcomes that respect the environment and respond to the voices of those we serve.”

Under the plan, the additional acreage would create space for expansive new garden areas at Stoneleigh, providing a broader platform from which to showcase the beauty and benefits of an ecologically sustainable approach to gardening. Early 20th century landscape designs by the famed Olmsted Brothers span both properties, which would be connected again for the first time since the portion known as Oakwell was subdivided off in the 1930s.

The buildings on the property would be restored and adapted, creating exciting improvements to the guest experience at Stoneleigh. As Stoneleigh is now, the portion that Natural Lands seeks to acquire would be placed under conservation easement with the Lower Merion Conservancy. The nonprofit purchasing the subdivided portion intends to enter into a mutually agreeable conservation easement agreement with Lower Merion Conservancy

Andy Gavrin, Lower Merion Township Commissioner, added, ”Protecting this historically and environmentally important property while finding alternative solutions to the School District’s need for playing fields has been a major focus of mine for quite some time. This agreement, in conjunction with the recent partnership for the use of the Polo Field for the Black Rock Middle School baseball and softball teams, truly results in a win-win-win solution. I am grateful to Natural Lands and Lower Merion School District for coming together, as well as to the members of the Lower Merion community who put so much time and energy into this vital conservation effort.”

Stoneleigh is open free-of-charge to everyone, year-round and hosts myriad community groups, from students to garden clubs to nature enthusiasts. The 42-acre public garden celebrates the beauty and importance of the natural world and gardening with native plants. The public is invited to learn more at stoneleighgarden.org.

Natural Lands is dedicated to preserving and nurturing nature’s wonders while creating opportunities for joy and discovery in the outdoors for everyone. As the Greater Philadelphia region’s oldest and largest land conservation organization, Natural Lands—which is member supported—has preserved more than 135,000 acres, including 40+ nature preserves and one public garden totaling more than 23,000 acres. Nearly five million people live within five miles of land under the organization’s protection. Land for life, nature for all. natlands.org.

Please note: “Natural Lands” is the organization’s official operating name and should be used instead of its legal designation (Natural Lands Trust, Inc.).

Lower Merion School District (LMSD) serves the 67,000 residents of Lower Merion Township and Narberth Borough. Established as one of Pennsylvania’s first public school districts in 1834, LMSD enjoys a rich tradition of achievement, innovation and community partnership and a longstanding reputation as one of the finest school systems in the United States. The District’s six elementary schools, three middle schools and two high schools provide a challenging, multi-disciplinary academic program and dynamic, co-curricular experience to about 8,700 students. LMSD.org

Media Inquiries:

Kirsten Werner, Senior Director of Communications

610-353-5587 ext. 267

267-222-0072 (mobile)

kwerner@natlands.org

Amy Buckman, Director of School & Community Relations

610-645-1978

267-473-1131 (mobile)

buckmaa@lmsd.org

###

Early spring is the season for removing Chinese mantis oothecae (or egg cases) at Stoneleigh: a natural garden.

Introduced to the United States in the 1800s. Unfortunately, these large predators are generalists with voracious appetites that will eat anything they can catch, including butterflies and bees. Considering Chinese mantids are nearly twice as large as our native Carolina mantis (Stagmomantis carolina) and much more abundant, they can have a greater impact on our beneficial insect populations. Chinese mantids (Tenodera sinensis) are non-native insects that were accidentally introduced to the United States in 1896 in Mt. Airy, Pennsylvania.

At Stoneleigh, we’ve been removing egg cases from our meadow and other perennial-dominated areas for several years. Our first year, we removed more than 350 Chinese oothecae from our meadow alone.

This year, volunteers and staff scoured several large garden areas and only found 68! By decreasing the population of this generalist, non-native predator and increasing the number of native plants, the garden is becoming more hospitable for our native butterflies, bumblebees, and pollinators every year.

To learn more about mantids and their egg cases, check out Natural Lands’ blog post at natlands.org/praying-or-preying.

Photo by Colin Purrington

Photo by Rachel Rhodes

A Carolina Chickadee makes its nest in the tree sculpture.

Photo by Samantha Nestory

At Stoneleigh: a natural garden, a London planetree—close cousin to the native American sycamore—has towered over the Main House for more than 150 years. Its pale, mottled branches have shaded the gardens below, inspired artists and poets, and offered shelter to songbirds and other critters.

Sadly, the tree is dying. Weakened by both sycamore anthracnose and canker stain, the London planetree was no longer safe and had to be scaled back dramatically earlier this spring. It now stands as an example of the value of dying and dead trees to the environment, a tree sculpture that will be planted with native vines.

A tree’s death can serve a purpose as vital as its life. Beetles and other insects bore into the softening wood, creating openings for fungal spores and bacteria. Over time, the core of the tree—the heartwood—softens and more insects arrive. Woodpeckers, nuthatches, and chickadees tap holes into the crumbling wood as they feast on the bugs, creating cavities for other bird species and mammals to use as nesting space or protection from winter’s chill. Mushrooms sprout from the bark while, on the ground, new plant species emerge in the newly available sunshine.

Every gardener knows that change is part of tending a garden. We invite you to visit Stoneleigh to watch how the London planetree changes in this new phase of its existence.

At Stoneleigh: a natural garden, a magnificent London planetree towers near the Main House like a living picture frame. Although we don’t have any specific records of its planting date, this tree is estimated to be at least 150 years old. Photographs from 1913 show the tree standing dozens of feet tall. It has become a familiar sight over the years as guests explore Stoneleigh. Students have written poems about its branches, and many people have enjoyed a seat under the canopy of its leaves.

Sadly, the London planetree is dying. This tree has sycamore anthracnose, a fungal disease that affects a tree’s ability to leaf out, thereby affecting its ability to photosynthesize. It also has sycamore canker stain, a more serious, frequently fatal pathogen caused by a different fungus. The tree was already in decline when Natural Lands acquired Stoneleigh in 2016. Our staff and expert arborists have been attending to it over the years, pruning dying branches, but we now must accept that the life of this tree is ending.

For the safety of our guests and to protect the historic structures on the property, we needed to scale back the tree. Arborists from Shreiner Tree Care removed most of the branches and topped the tree, leaving the central trunk, called a snag. This will prevent injury or damage from falling branches. It will also allow the tree to continue to play a part in the ecosystem of the garden.

When a tree dies, its death can serve a purpose as vital as its life. As the tree is dying, some insects, such as metallic jewel beetles, move into the tree creating tunnels and openings for fungal spores and bacteria. Over time, the central part of the wood core of the tree, known as the heartwood, will begin to soften. As the heartwood decays, more insects arrive, burrowing and building, while woodpeckers tap on the softening wood to feast on the bugs. Mammals crawl into open holes, taking shelter in the heartwood against the winter’s chill or building nests to rear their young in spring. Native mushrooms sprout from the bark like open fans in orange and white. New plant species thrive in the newly available sunshine, offering food and shelter for myriad species.

When a tree dies, its death can serve a purpose as vital as its life. As the tree is dying, some insects, such as metallic jewel beetles, move into the tree creating tunnels and openings for fungal spores and bacteria. Over time, the central part of the wood core of the tree, known as the heartwood, will begin to soften. As the heartwood decays, more insects arrive, burrowing and building, while woodpeckers tap on the softening wood to feast on the bugs. Mammals crawl into open holes, taking shelter in the heartwood against the winter’s chill or building nests to rear their young in spring. Native mushrooms sprout from the bark like open fans in orange and white. New plant species thrive in the newly available sunshine, offering food and shelter for myriad species.

The London planetree after the process of scaling down. Vines will be planted around the base of the tree in the spring. Photo by Sam Nestory

Our beloved London planetree will still be a part of the garden. This spring, staff will plant a selection of native vines at the base of the tree, including American wisteria, which has impressive lavender blooms. These vines will be trained up the tree and along the remaining limbs over the next several years, creating a beautiful floral display every spring. The reduced canopy will also provide an opportunity to add more sun-loving native plants to the surrounding garden spaces, which will increase the biodiversity in this area.

The London planetree is a hybrid of the American sycamore. While it shares many traits of the sycamore, it is not a native species to our region. This transition will allow us to plant a variety of native, sun-loving species in the absence of the once dense and leafy canopy, a continuation of our commitment to planting native species as nonnative plants come to the end of their lifecycle.

Every gardener knows that change is part of tending a garden. In nature, endings are intimately tied with beginnings, decay nurtures new growth. We invite you to visit to see our progress this spring as we transform the tree to a snag, and to come back to watch how we grow, change, and bloom.

In the fall of 2021, Villanova University’s Nature Writing Workshop met at Stoneleigh: a natural garden to take inspiration from that unique space.

Photo by David Korbonits

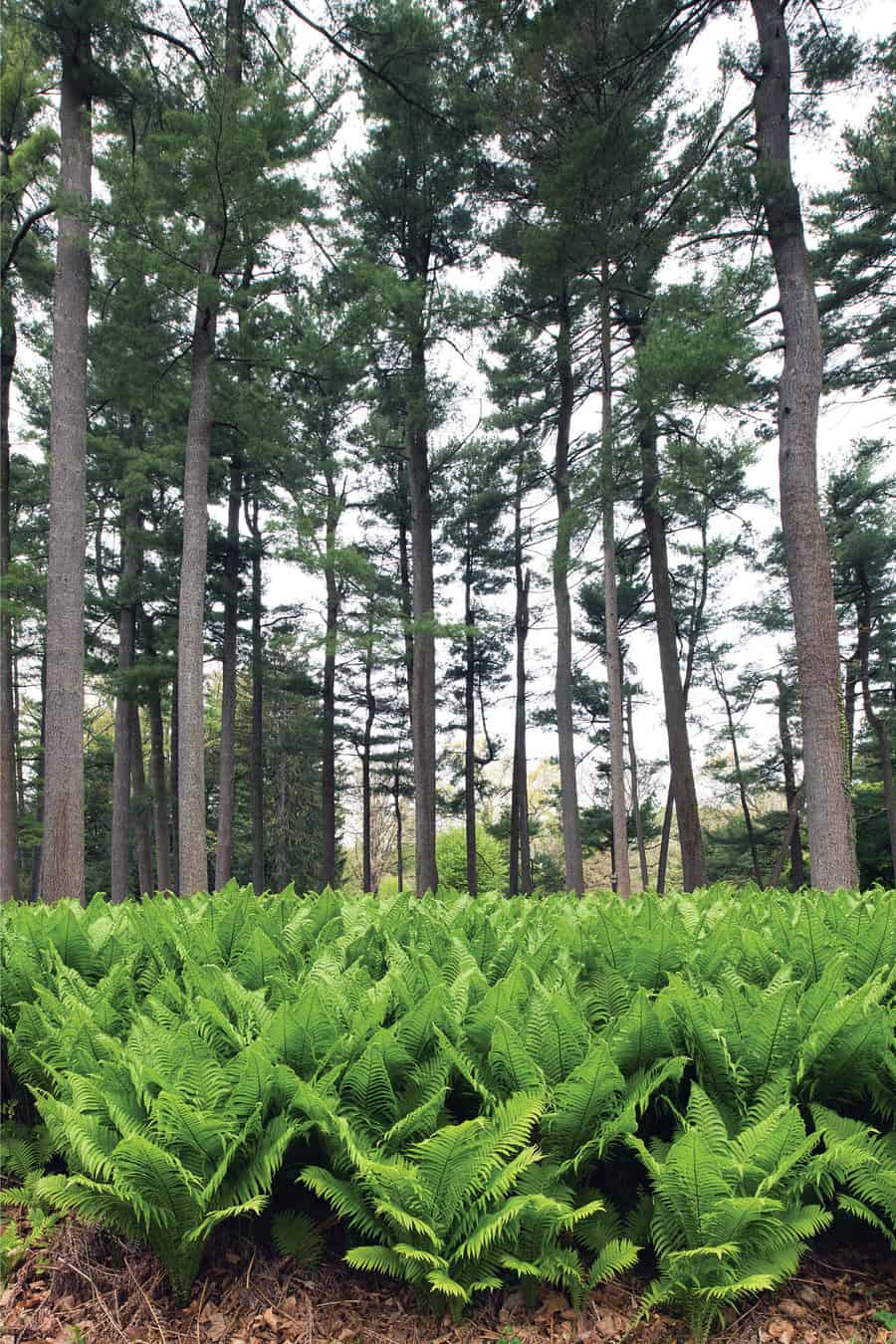

It was the garden’s copse of pines that inspired Ciara Coulter, a chemical engineering major and English minor.

“They are incredibly beautiful and supremely tall, and I was struck by how soldier-like they were in stature and uniformity. Beneath them lies no brush save for a carpet of ferns. I began to ponder: why was there so little middle growth? What might the relationship between these two plants be? Quite taken by this scene, I explored one whimsical possibility.”

There is a Grove of White Pines

Small and sleepy, the first among plants grew under starlight. Like nightcrawlers, they sprawled across the earth, a dense carpet, soft and muffled. In a dreamlike daze, they whispered to one another, roots hugging and tendrils swaying, dancing ever so slightly. Their spectral chorus called to every plant, uniting them, sustaining them in song. In their stupor they swam, but something lurked beneath their soft, unchanging hymns. Restlessness. And then the deep night sky started to brighten.

One lone star began to grow, to bolden amongst a sea of speckled sky.

It just got a little easier for guests of Stoneleigh: a natural garden to learn the native plant species that comprise the beautiful, biodiverse, and beneficial landscapes there. Chris Polidore, the Stoneleigh summer intern for 2021, installed a whopping 501 plant identification labels during his internship.

“Stoneleigh is a botanical garden, which means we display documented collections of plants for public education as well as for their important place in the ecology,” said Stoneleigh Director Ethan Kauffman. “Plant labels allow our guests to note information like the genus, species, and cultivar so they can know what to look for when shopping for plants for their own backyards. They help our guests learn more about the world of horticulture.”

A grant from the American Conifer Society funded the labels for Stoneleigh’s conifers and a portion of the installation time. The Garden Club of Philadelphia provided additional support.

The intern program was funded in perpetuity with an initial gift from generous donors who wish to remain anonymous and has been augmented with a meaningful contribution in memory of longtime Natural Lands member and volunteer Dr. Martha Turner-Leonetti.